Aiden Markram was run out for 19 in the second ODI against Australia at a point when South Africa were starting to dominate the Aussie attack. It was a costly wicket, and there were three reasons why this should never have happened, writes SIMON LEWIS.

Markram was looking in pretty good nick during his brief inning of 19 off 17 balls, having hit two fours and a monster six. At the same time, there were signs that he was feeling under pressure, which is not surprising considering that he has gone more than 10 innings without reaching 50, even though he got off to a good start in at least eight of those innings. He’s been looking superb at the crease.

Right now he’s batting like a steam train racing at full speed, which is great to watch but my concern is that he is playing high-risk cricket too early in his innings. I’d like to see him look to bat right through an innings and forget about chasing boundaries – dial down the positive cricket, at least until he’s secured his 50.

I think more of the Proteas batters could benefit from trying this approach as well. Try to bat through an entire inning with your focus on finding the gaps to push ones and two, and just let the boundaries come as a byproduct when the bad balls present themselves for punishment. The Proteas appear to be looking to force the runs with overly attacking strokes too early in the innings, and this is what is continually putting their wickets at risk.

This is the experimental phase before the World Cup, and Markram is a key figure in those World Cup plans, so using the time now to try a different approach to his innings can surely only serve South Africa well in the months to come. Set yourself a target of scoring 50 in your next innings at all costs, even if you take 100 balls to do it. Imagine that it’s the World Cup final and, to win, you need to score 50 off 100 balls – and then play like your life and the hopes and dreams of 60 million South Africans depend on your innings.

The run-out

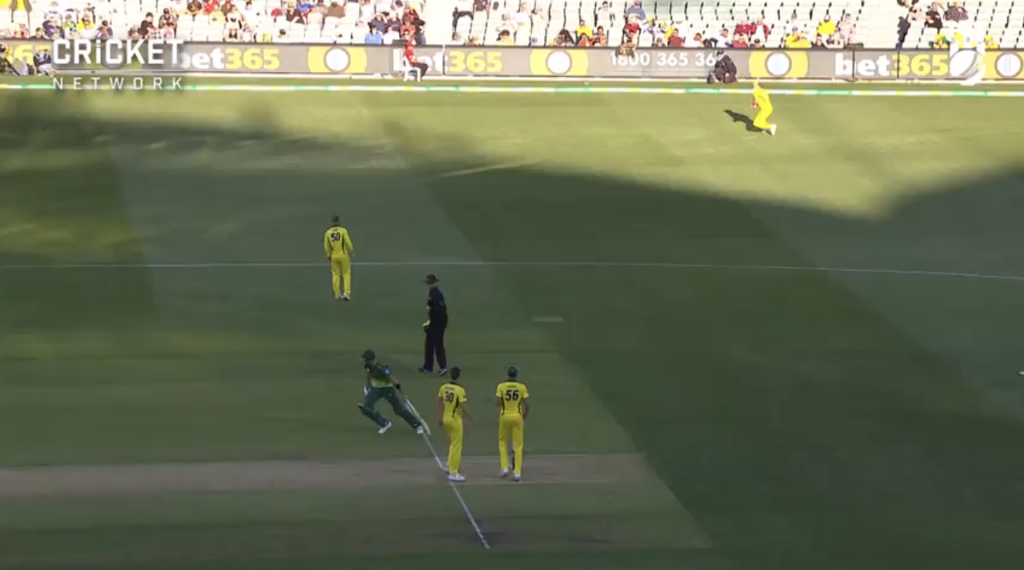

Marcus Stoinis chased Reeza Hendricks’ legside push looking like a man towing a caravan (‘He’s chased it flat out,’ said commentator Shane Warne describing Stoinis’ effort in the field, but then everything is relative), and even his slide and pickup looked sluggish. His throw to the opposite end, however, was world-class, as was the collect and crash into the stumps by keeper Alex Carey.

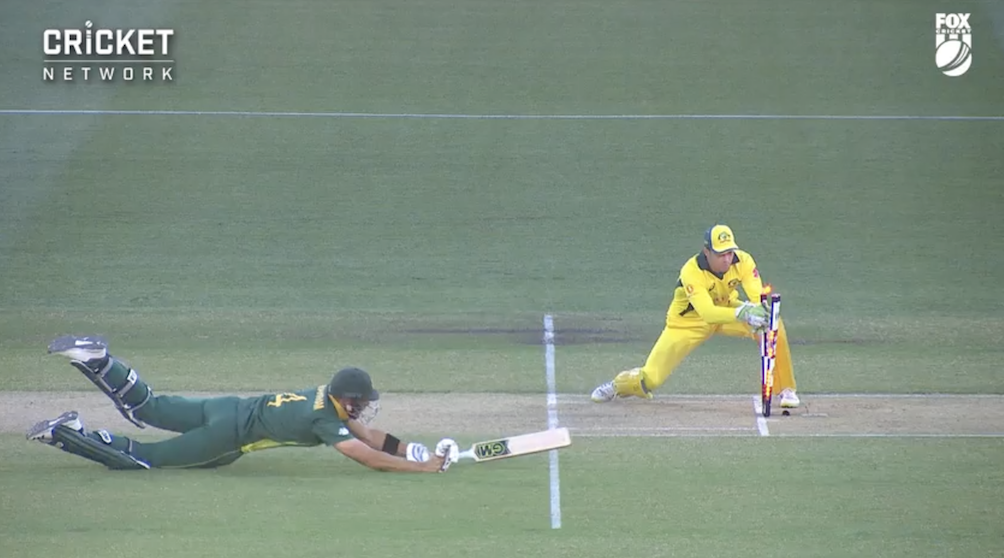

It was a brilliant display of throwing from the deep and collecting by the keeper and, to his credit, Markram gave it his all in trying to make his ground, including a brave sliding dive right at the end. He was unlucky that his bat bounced up as he dived forward – if it had been grounded he wouldn’t have been given out.

When diving at such speed it’s impossible to control your bat in that position, so that was simply bad luck. However, there are three factors that contributed massively to this dismissal.

CLICK PHOTO TO WATCH THE MARKAM RUN OUT

Ironically, if you watch any international match today, you will see a lot of very experienced batters backing up and running poorly between the wickets. It’s a surprise because cricket is all about runs and wickets, yet so many batters are handicapping themselves when it comes to backing up and running between the wickets.

When South Africa played India at Kingsmead in 1992 in the first home Test since isolation, my cameraman Thomas Turck captured images of cricketing legends Peter Kirsten and Kepler Wessels walking out of their crease on a number of occasions before the bowler had delivered the ball. We published these pictures in The Googly magazine (ironically, a publication which had been co-founded by Peter Kirsten himself) a few days after Kapil Dev infamously Mankaded Kirsten in an ODI at Port Elizabeth.

Mankad is there to allow the bowler to – rightly – run out a batsman who is trying to cheat by stealing ground when backing up. Kirsten wasn’t trying to gain an unfair advantage, which was why the incident created such a furore, but Kapil Dev remained within his rights and within the law, as Kirsten had reportedly been warned about his backing up on a number of occasions.

For all of us who haven’t played high-level cricket, we can’t begin to understand the pressure and stress players are under, so it’s wrong to criticise either Kapil Dev or Kirsten in that situation. However, the onus lies with the batter at all times to protect his or her wicket. Don’t give the bowler the opportunity to Mankad you and then you can’t be Mankaded. Simple.

However, let’s get back to Markram’s run out, and the three ways that his wicket could have been saved.

1) Don’t risk your wicket on your teammate’s call

The old rule says that the batter running to the danger end makes the call, as he or she is the one facing the greatest danger of being run out. That’s a good rule, but batters need to preserve their wickets first and foremost, especially in these days of super professional fielders.

In 1990 I was batting for a UCT/UPE combined XI in an SA Universities Week match against Pietermaritzburg University. My batting partner was Grant Morgan, the current Dolphins and Durban Heat coach. I hit a straight drive down to the long on boundary, we ran two and then I made the call to go for the third because I was running to the danger end … and because I wanted the thrill of beating the fielder in question.

As I sprinted to the safety of the bowler’s crease, I was shocked to see the ball whizzing over my head at great pace. I turned and saw the ball land in the keeper’s gloves and, in one movement, he smashed the stumps over. Morgan, diving, was probably run out but, mercifully for me, was given not out by the umpire. There was a lot more benefit of the doubt for batters in those days.

The fielder in question was Jonty Rhodes, and my enthusiasm to challenge him to a ‘race between the wickets’ overlooked the fact that he had a superhuman ability to throw a ball further and more accurately than us mere mortals.

In those days Jonty Rhodes was already heralded as a cricketing star at provincial level and a world-class fielder, but today the level of fielding in cricket is so high that running between the wickets has become a high-risk venture. While white ball cricket has placed a higher premium on boundaries than wickets, the golden rule remains that you can’t score runs in the changing room.

Someone has to make a call of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ when batting, but that doesn’t mean that the other partner has to go along with the call. Say no if you think there’s too much risk to either of your wickets … and use all 300 balls available to you in a 50-over match. There’s a delicate balance between taking a risky single and putting pressure on the fielding side, but at all times rather err on the side of giving up on a single in order to save your wicket, especially during the first 40 overs of an innings.

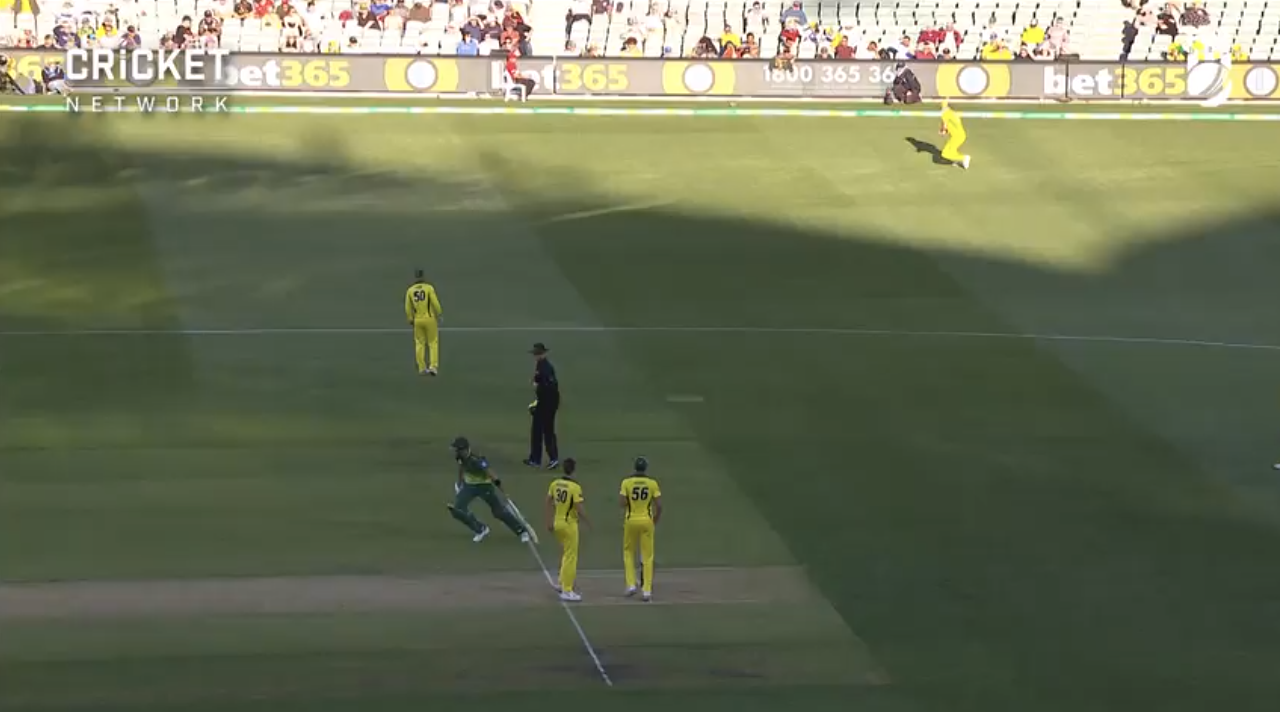

2) Don’t turn blind

This was a schoolboy error by Markram: when he turned for the third run, his back was facing towards the fielder. It’s a basic error but not a massive one, as batters will often still make their ground even if they turn blind, although it does make it that little bit harder to judge the safety of the run.

Possibly Markram didn’t think there was a run in the first place, which might be why he was turning blind. Perhaps he wasn’t even contemplating that the third run was on? Either way, he made an error: if he didn’t think there was a run, he should have placed the value of his wicket above that of a risky single and called ‘no’ loud and clear to send Hendricks back to his crease. Turning blind also made it that little bit harder for him to judge the wisdom of the single.

As you can see in the screenshot below, Stoinis was on his feet and about to release the ball while Markram was still on the crease. With the benefit of ‘hindsight’ (ie having his back to the fielder) that was always going to be a risky single.

It was an error that cost Markram his wicket, and it cost him and the Proteas dear. Batting at three in an ODI you often have time to score a century, and that’s where Markram’s focus needs to be. Not stealing every single or crushing the bowlers to the boundary from ball one. He needs to play the long game and bat 30-40 overs an innings. Yes, get a bad ball and hammer it, break the fielders’ fingers, but allow yourself a bit more time to settle at the crease. He’s a man with big runs ahead of him in his future, as is Reeza Hendricks, but they both need to ease off on the throttle at times.

If South Africa hadn’t lost Markram at that point then there’s every chance that the Proteas would have turned the result of the match around to secure the series. As it is, the Proteas now face a battle to win the series, with Australia’s confidence on a high after breaking their record seven-match losing streak.

3) Slide your bat in and turn quick

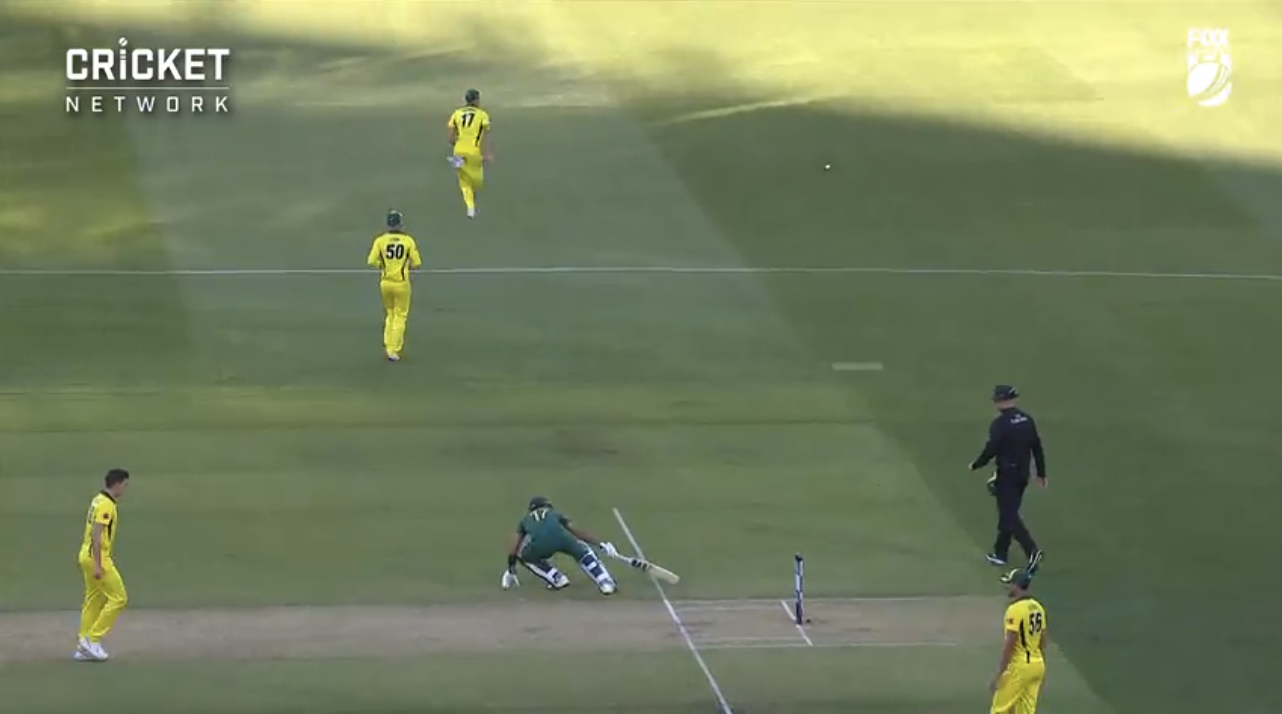

Without a shadow of a doubt, if Markram had followed this third rule then he would have made his ground and saved his wicket. He was given out after the on-field umpire asked the TV umpire to assist with the decision because it was such a close call. As it was so close, if he could have saved a split second at some point then he would have would have been home safe, albeit still dirty.

How could he have saved that split second?

When Markram turned for the third run, he hadn’t slid his bat into the crease the way he normally would when running. For some reason, he ran right up to the crease and his foot was actually on the line.

Normally your foot would be two or three feet away from the line and you would slide your bat along the ground to pass the popping crease, then turn and run back down the pitch. That’s the standard way batters run between the wicket (see below). If Markram had slid his bat in like this he would definitely have made his ground, although it was still a risky single that possibly should have been turned down.

The new golden rule should be to ALWAYS turn and slide your bat so that you are ready and in a position to take the next run. If you’re willing to take a chance on a risky single, then you should really be willing to push the envelope further with your running between the wickets. And this applies to all batters at international level (more on this issue next week!).

In conclusion

Markram and Hendricks have the power, the strokes and the composure to play World Cup-winning innings for the Proteas, and they both look beautiful at the crease. They’re a joy to watch. My hope is that they are encouraged to take the time to play themselves in more during their innings over the next six months and to also be a bit more careful running between the wickets.

It would be a tragedy for any of the team to lose their wicket to a similar dismissal (especially in the World Cup final) so, hopefully, lessons will be learned from this series as well as Markram’s run out.

CLICK PHOTO TO WATCH MARKAM’S MASSIVE SIX

Markram’s monster six off Mitchell Starc was as clean and pure a strike as you can hope to see, travelling 95 metres before being superbly caught by a man in the crowd.

CLICK PHOTO TO WATCH MATCH HIGHLIGHTS

Footage & visuals: Cricket Australia