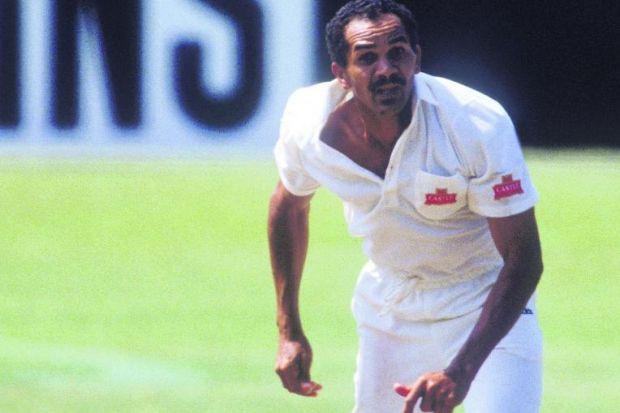

All over the world, young black activists are fighting for equality and social justice. In South Africa, the most notable such uprising happened today in Soweto in 1976. It culminated in the end of apartheid, a system of racial oppression that affected all facets of society, including sport, and later paved the way for Henry to become the first non-white cricketer to represent the Proteas in the post-isolation era.

I remember watching that match against India with a great degree of pride and expectation. Not only did it represent the dawn of a new era in South African cricket, but Henry was a former member of my club, Avendale, so I had a personal investment in his rise.

Bob Woolmer coached him at Avendale and would often point to him, and later Herschelle Gibbs, as evidence that a cricketing renaissance was coming.

However, change has been frustratingly slow since, not least of all because there has been a focus on quotas at the game’s elite levels for too long. Creating the landscape for equal opportunity, which includes a concerted focus on resourcing grassroots cricket in the country’s traditionally underprivileged communities, has been overlooked to the detriment of development and representation.

It is part of the reason that in nearly three decades since Henry took the field in India and four decades after hundreds of lives were sacrificed in Soweto, there have been only been a small number of black players (for the purposes of this piece this includes black African, coloured, Indian and Muslim players) who have played for the Proteas, and an even smaller number who can be considered truly world class.

It is an indictment of the system that the first black African to score a Test century for the Proteas only did so just four years ago. Temba Bavuma, at the time only the sixth black African to represent the Proteas, achieved the feat against England at Newlands in 2016.

Looking around the domestic scene now, it is hard to predict where the next black African Test, ODI or T20 century will come from. This is deeply disappointing and shouldn’t be the case 28 years post isolation.

Encouragingly, there are a clutch of gifted black fast bowlers playing international cricket, Kagiso Rabada chief among those. Rabada and his ilk benefited from opportunities at some of South Africa’s leading schools, universities and clubs. This signifies progress.

The next frontier should be the emergence of more Makhaya Ntinis, players who come from rural, township and community clubs and rise to the elite levels of the game.

But the structures which feed the professional system make that a pipe dream at present. Those not spotted by top schools and universities have to toil in club cricket, which has been neglected and poorly managed across the country for longer than I care to remember.

Programmes meant to develop black players in club cricket have largely failed. For example, Bavuma’s former club, Langa, are in year three or four of a programme aimed at developing black African players (this is the second time in the last decade this approach has been trialled). In that period they could not be relegated from Cape Town’s Premier League. I can’t remember them winning a match. In fact, they struggle to even compete. Other black African clubs in the city enjoy the same immunity in lower divisions but struggle equally.

The concept is good but they’ve been offered next to no resources to make meaningful improvement. I’m told the situation is similar in other black cricketing hotbeds around the country.

There isn’t a lack of talent or appetite for the game in the black community. But the support and resourcing don’t match the talent and appetite. This means the opportunity for them to rise is unequal to their white counterparts. Equal opportunity at these levels is the path to eradicating the quota system.

This must be the key focus area if we are to develop a pool of professional prospects that are representative of our country.

Today we celebrate an uprising that defined the nation. We are still waiting for a (non-violent) cricketing uprising that will define the nation.