During a Test match in Mohali in December 2008, Andy Flower sat down in the dressing room next to Kevin Pietersen and offered to help, writes LAWRENCE BOOTH.

Flower was England’s deputy coach at the time – Peter Moores was at the helm – and had been a Test captain himself with Zimbabwe. This was only Pietersen’s third game in charge and, in the previous match, India had chased down 387. The least England’s new leader needed was a bit of help. Flower’s gesture seemed friendly enough.

Pietersen didn’t see it that way. He regarded Flower’s behaviour as a ‘corporate move’. In KP: The Autobiography, Pietersen parodies the motives of his bête noire: ‘Deputy CEO Andrew Flower has been designated to use a limited amount of empathy with a talented but troubled employee.’ According to Pietersen, Flower approached him because he was ‘preparing for life after Moores’.

Elsewhere in his new book, Pietersen reflects on England’s 3-1 Ashes triumph in Australia in 2010-11. Recalling the series Test by Test, he begins at Brisbane, where he concludes: ‘I don’t get to bat in the second innings. Rain affects play and we end up with a draw.’ There is no mention of the role played by England’s second-innings 517-1, a total that helped soften the Australians up for the games that followed. And they would lose three of the next four by an innings. But, well, Pietersen didn’t bat, so never mind 517-1 …

A third vignette. When Pietersen returns to the England dressing room one summer after fun times at the IPL, he embarks on a story in front of his teammates: ‘So me and Virat Kholi [such a good buddy that Pietersen misspells his name] and the boys …’

The next paragraph is made up of a single line: ‘Eyes glaze over.’ Pietersen is unable to comprehend the reaction.

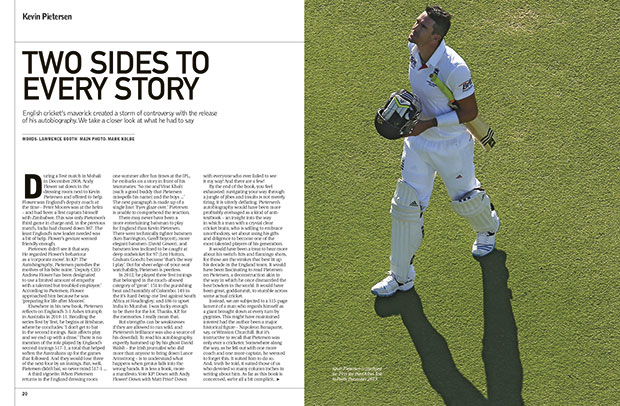

There may never have been a more entertaining batsman to play for England than Kevin Pietersen.

There were technically tighter batsmen (Ken Barrington, Geoff Boycott), more elegant batsmen (David Gower), and batsmen less inclined to be caught at deep midwicket for 97 (Len Hutton, Graham Gooch) because ‘that’s the way I play’. But for sheer edge-of-your-seat watchability, Pietersen is peerless.

In 2012, he played three Test innings that belonged in the much-abused category of ‘great’: 151 in the punishing heat and humidity of Colombo; 149 in the it’s-hard-being-me Test against South Africa at Headingley; and 186 to upset India in Mumbai. I was lucky enough to be there for the lot. Thanks, KP, for the memories. I really mean that.

But strengths can be weaknesses if they are allowed to run wild, and Pietersen’s brilliance was also a source of his downfall. To read his autobiography, expertly hammed up by his ghost David Walsh – the Irish journalist who did more than anyone to bring down Lance Armstrong – is to understand what happens when genius falls into the wrong hands. It is less a book, more a manifesto. Vote KP! Down with Andy Flower! Down with Matt Prior! Down with everyone who ever failed to see it my way! And there are a few!

By the end of the book, you feel exhausted: navigating your way through a jungle of jibes and insults is not merely tiring, it is utterly deflating. Pietersen’s autobiography would have been more profitably envisaged as a kind of anti-textbook – an insight into the way in which a man with a crystal clear cricket brain, who is willing to embrace unorthodoxy, set about using his gifts and diligence to become one of the most talented players of his generation.

It would have been a treat to hear more about his switch-hits and flamingo shots, for those are the strokes that best lit up his decade in the England team. It would have been fascinating to read Pietersen on Pietersen, a deconstruction akin to the way in which he once dismantled the best bowlers in the world. It would have been great, goddammit, to stumble across some actual cricket.

Instead, we are subjected to a 315-page lament of a man who regards himself as a giant brought down at every turn by pygmies. This might have maintained interest had the author been a major historical figure – Napoleon Bonaparte, say, or Winston Churchill. But it’s instructive to recall that Pietersen was only ever a cricketer. Somewhere along the way, as he fell out with one more coach and one more captain, he seemed to forget this. It suited him to do so. And, truth be told, it suited those of us who devoted so many column inches to writing about him. As far as this book is concerned, we’re all a bit complicit.

But, ultimately, it’s his book. Late on, there is a flash of clarity, and it comes as a crushing revelation for the reader. ‘There should have been more cricket in these pages,’ confesses Pietersen, ‘but there was a story that had to be told.’

The story, it turns out, is not necessarily the one Pietersen wanted to tell. In his own mind, his sacking by England earlier this year was the result of disastrous man management, mainly by Flower – who is dismissed as the ‘Mood Hoover’ with such grinding remorselessness that Pietersen sounds like the pub bore, desperate to retell his joke to those who pretended not to hear it the first time.

He also slags off many of his teammates, who he says contributed to a culture of bullying in the dressing room. The claim is based on two charges. The first is that certain players – Prior, Graeme Swann, Jimmy Anderson, Stuart Broad and Tim Bresnan – would shout at colleagues when they misfielded. The second is a fake Twitter account called @KPGenius. It was started by a friend of Broad and caused more amusement in the dressing room than Pietersen felt comfortable with. When he advises teammates in his book to adopt a thicker skin over the stream of Twitter abuse directed at them by his cheerleader Piers Morgan, you weep quietly for his self-awareness.

Instead, Pietersen reveals himself – inadvertently, on the whole. His interpretation of Flower’s behaviour in Mohali is at best uncharitable, and this was before his relationship with England began to deteriorate after his sacking as captain at the start of 2009. His failure to mention England’s staggering rearguard in Brisbane is either wilful or negligent (and neither reflects well on his sense of team spirit). And his obvious irritation at his teammates’ lack of interest in another IPL anecdote suggests a fatal inability to gauge a mood.

This last trait, perhaps more than anything, turned out to be Pietersen’s undoing. Asked during one of his innumerable book-promoting interviews what he most regretted about his England career, he insisted his main crime had been an excess of honesty. This could have been a cute answer, the kind given at job interviews by candidates invited to assess their weaknesses. And it’s certainly true that Flower would occasionally despair at what he felt was the conflict-averse nature of the England dressing room.

But there’s a way of being honest – and there’s KP’s way of being honest. When Hugh Morris, then the managing director of the England team, phones Pietersen to inform him of his sacking, Pietersen calls him a ‘weak prick’. Not just ‘weak’, but a ‘prick’ too – an unpleasant flourish that says more about its author than its target. Alastair Cook is, according to Pietersen, a decent guy, but is still dismissed as ‘Ned Flanders’, the nice but naive Bible-basher from The Simpsons. And the amount of industrial language within these pages makes you doubt his claim at the end of chapter four that he’ll be in trouble with his dad for using the relatively gentle ‘he doesn’t piss about’.

The book paints a vivid picture of a man incapable of viewing himself as others do. A more perceptive soul might have understood the problems this characteristic might cause in a sport which remains – despite its emphasis on individual skill – a team endeavour. But this failing is at the heart of his fallouts with Moores, Andrew Strauss, Cook and Flower, to name but a few. Fatally, Pietersen just can’t see it.

The paradox is that he has some coherent points to make about the way he was treated. Why, he wonders, did Swann get away with damning Pietersen’s captaincy in his own autobiography when Pietersen was fined for criticising the commentary of Sky TV’s Nick Knight on Twitter? Why was Strauss, as captain, allowed to sit out a tour of Bangladesh when Pietersen wasn’t even allowed to fly home for a couple of days from a trip to the Caribbean to be with his family? And why was the @KPGenius Twitter account allowed to run unchecked for so long when it clearly distressed Pietersen?

Neither does Flower emerge in a complimentary light for his handling of the whitewash in Australia. If Pietersen’s version is to be believed, Flower lost control of the tour and railed consistently about the damage each new defeat was doing to his team’s legacy. The two men plainly didn’t get on. Pietersen seems to think this was mainly Flower’s fault, and happily explains away England’s successes during Flower’s reign as a consequence of coaching a strong squad.

What seems in little doubt is that the ECB mishandled Pietersen’s sacking, to the extent that a sizeable minority of England fans have ended up taking his side. A confidentiality agreement between the two camps came to an end in October, at which point – the ECB had assured us – the public would understand exactly why Pietersen was shown the door. And yet, aside from a couple of leaks, convincing explanation came there none. The ECB have helped to turn Pietersen into a martyr.

In fact, the explanation needn’t have detained our finest administrative minds for too long at all. The basic truth is that Pietersen was widely regarded as a pain in the backside. When he was scoring runs, this wasn’t a problem. When he wasn’t, it was. And he’s now 34, with creaking joints.

At the London Sportswriting Festival, I chaired a panel of journalists who were debating the question of whether Pietersen had been more sinner than sinned against. At the start and the end of the hour-long session, I asked an 80-strong audience for a show of hands. The figure remained unchanged: around two-thirds chose sinner. It was curiously typical of the KP debate: few seem inclined to change their minds.

And, enjoyable though the discussion was, it also felt like a shame that it had to happen in the first place. As one of the festival organisers said to me: ‘I remember the Pietersen era as one of English cricket’s most successful. We won three Ashes, topped the Test rankings, lifted a World Twenty20 and beat India in India. But now it’s all gone sour.’

He has a point. The effect of Pietersen’s book is to take his teammates down with him – their achievements, their memories, their pride. Pietersen did have genuine cause for grievance, but so do most people who played international sport for 10 years. Opinions differ, egos clash. What, frankly, did he expect?

As ever, perhaps the most incisive observation came from an outsider. During his whirlwind promotional tour, Pietersen found himself being interviewed on a prime-time TV slot along with John Cleese and Taylor Swift. The host was Graham Norton, a famously direct and mischievous Irishman with no great affection for sport, let alone one which can last five days and still end in a draw. At one point, Norton tells Pietersen: ‘Reading the book, it strikes me that maybe, just maybe, team sport’s not for you.’ The audience erupts and, to his credit, Pietersen joins in the laughter.But it was the jibe of a Shakespearean court jester: witty and wise, sardonic and sad. Pietersen really ought to be remembered exclusively as a batting superstar. This book puts paid to that.

Not for the first time in his career – and now literally so – Kevin Pietersen has been the author of his own downfall.

This feature appears in the current issue of Business Day/Sunday Times Sport Monthly.