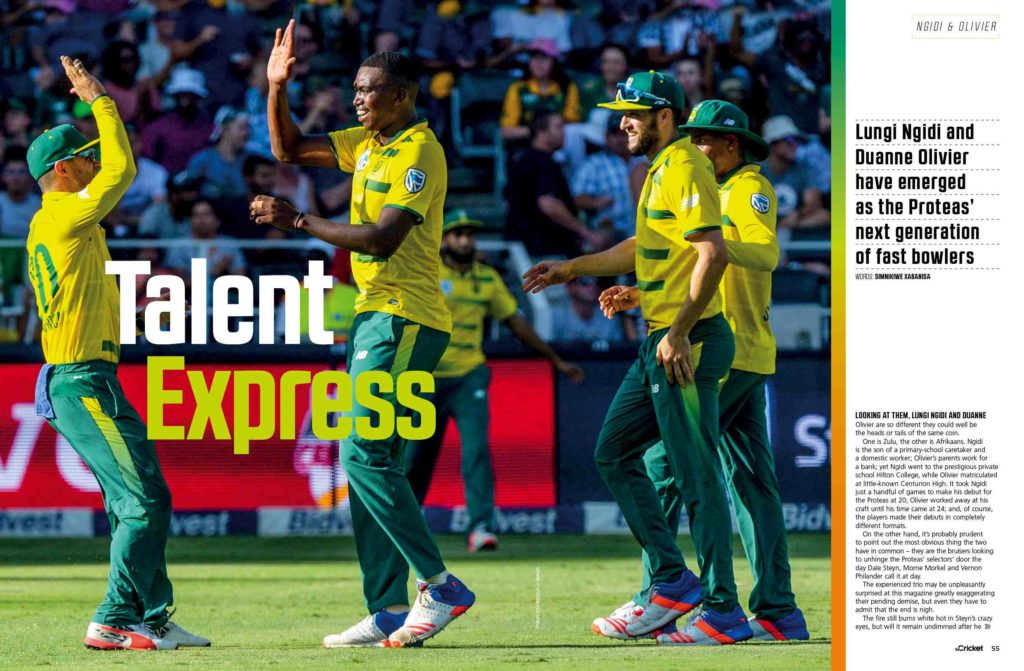

Lungi Ngidi and Duanne Olivier have emerged as the Proteas’ next generation of fast bowlers, featured in the latest edition of SA Cricket magazine.

One is Zulu, the other is Afrikaans; Ngidi is the son of a primary school caretaker and a domestic worker, Olivier’s parents work for a bank; yet Ngidi went to the prestigious private school Hilton College, while Olivier matriculated at little-known Centurion High; Ngidi literally took a handful of games to make his debut for the Proteas at 20, Olivier whiled away at his craft until his time came at 24 and, of course; the players made their debuts in different formats.

On the other hand, it’s probably prudent to point out the most obvious thing the two have in common – they are the bruisers looking to unhinge the Proteas’ selectors’ door the day Dale Steyn, Morne Morkel and Vernon Philander call it a day.

The experienced trio may be unpleasantly surprised at this magazine greatly exaggerating their pending demise, but even they have to admit that the end is nigh.

The fire still burns white hot in Steyn’s crazy eyes, but will it remain undimmed after he gets the five wickets he needs to overtake Shaun Pollock’s national record 421 Test wickets? And how long will that famously wiry but increasingly fragile body hold?

Family man Morkel may be fit again after a spot of back trouble, but his priorities are changing to the point where multiple seasons on the international cricket grind aren’t really his prospects.

And while Big Vern has been at one with his mesmerising mix of control and downright sorcery with the ball over the last seven months or so, he has been doling out his instalments of magic in between bouts of ankle issues.

Which brings us to Ngidi and Olivier, two men who – injury permitting – could form a petrifying pace attack with Kagiso Rabada for years to come.

At 1.90m and 95kg (Ngidi) and 1.94m and 89kg (Olivier), both extract bounce from the wicket and bowl at a similarly uncomfortable 140km/h, with the latter visibly lively while the former looks more deceptively so.

On being seen as the coming men of South African fast bowling, they take different things from being mentioned in such exalted company but one can’t mistake the underlying modesty. Ngidi says it can only be motivation while Olivier prefers to keep his head down.

‘When people first started talking like that I got nervous because those are pretty much legends of our game,’ says Ngidi. ‘Hearing your name mentioned along theirs at 20 can be a bit daunting, but having them come to you and congratulate you, you think “maybe I can do this”.

Having played over 50 first-class games before his Test debut against Sri Lanka in January, Olivier prefers to look at the queue in front of him and the body of work those men already have: ‘It’s one thing to be mentioned in the same breath as Steyn, Morkel and Philander, but they’ve been doing so well for years and I’ve only played in one game [where he took five wickets]. I’ll wait for my chance and be grateful if it comes again.’

But clearly the bug has bitten, if the way he helped the Knights charge over the finishing line in winning the Sunfoil Series is anything to go by. In the end, Olivier took a series-topping 52 wickets at 18.13 in the tournament with teammate Marchant de Lange a distant second with 34.

Olivier does allow himself to look forward to working with Rabada in future: ‘He’s quality and has done wonders for South African cricket at only 21. He’s obviously the future and working with him and Vernon Philander was an honour for me.’

Perhaps fittingly for men with seven (Ngidi) and 61 (Olivier) first-class games, their preference of format is varied.

‘I love both but they come with different tests,’ Ngidi explains. ‘I don’t really have a favourite but T20 (where he made his sensational debut against Sri Lanka) is on the top of my list at the moment. I know red-ball cricket is the ultimate but with T20 you’ve got to be on the button from the first ball.

‘With red-ball cricket you can bowl three bad overs and still have time to get it back together.’

For Olivier there is no contest – the longer format of the game is the be all and end all. Yet for all their different upbringing, approaches and the fact that they barely know each other, the similarities in their progression are remarkable.

When they were in Grade 9, both were sat down by their high school coaches and told to choose between rugby and cricket.

Ngidi, a burly inside centre, says Hilton College Dean of Sport Shane Gaffney broke the bad news to him: ‘He told me he’d coached guys with cricket talent before (Dominic Hendricks and Temba Bavuma at St David’s in Johannesburg) and he felt I would go down the same path.

‘I guess I made the right decision because this has been an amazing journey. I’ve got a lot to thank cricket for.’

Having already been given the talk by his coach Johan Coetzee – now a domestic umpire – at his school, Olivier, a rangy fullback who had been a sprinter in primary school, had his decision made for him when he tore knee ligaments at around the same age Ngidi was encouraged to give up rugby.

Believe it or not, both then suffered stress fractures around Grade 10 and 11, injuries they made full recoveries from thanks to some remedial work being done on their actions – Ngidi to get his ‘straight lines’ aligned and Olivier to be more front-on upon delivery.

Unlike most sportsmen, both have insisted on continuing with their studies. Ngidi is a third year Labour Law student at Tuks, while Olivier studies Business Management through Unisa.

Getting an education out of cricket was probably always the idea for Ngidi, who would never have attended Highbury Preparatory School or Hilton had it not been for cricket bursaries. While he admits to having felt the odd man out among his rich kid peers at school.

‘I felt it but I didn’t let it get to me,’ he remembers. ‘I used it as motivation because I used to look at the parents and think “one day I’ll be in a position to send my kids to a school like this”. Also, my parents might be domestic workers but we all had the same opportunities at the same school.

‘So I asked myself, what was stopping me from achieving whatever I want in life?’

The clincher about the similarities between Ngidi and Olivier, who are laidback and soft-spoken, is that they both listen to house music. In explaining his love for Euphonik and DJ Kent, Olivier is very much aware of breaking the stereotypes: ‘I know I’m Afrikaans, but I don’t listen to Afrikaans music.’

What with the similarities, who would be favourite to be chosen to replace Steyn et al if the decision had to be made tomorrow? Olivier’s record of 253 wickets at 20.49 from 61 games would suggest he is the more ready-made option.

But while Ngidi has only played seven games, he has made a habit of adjusting quickly to higher levels. The number 21 he wears at franchise level is supposed to be the age at which he hoped to have made his franchise debut, and we all know how far he’s come already.

It’s a theory backed up by the fact from the day he spearheaded Hilton’s bowling attack from 16 he has always found himself having to do it over and over at all levels.

So what would the decision be? Well, if you tossed a coin the new ball would be in safe hands, regardless of whether it fell on heads or tails.