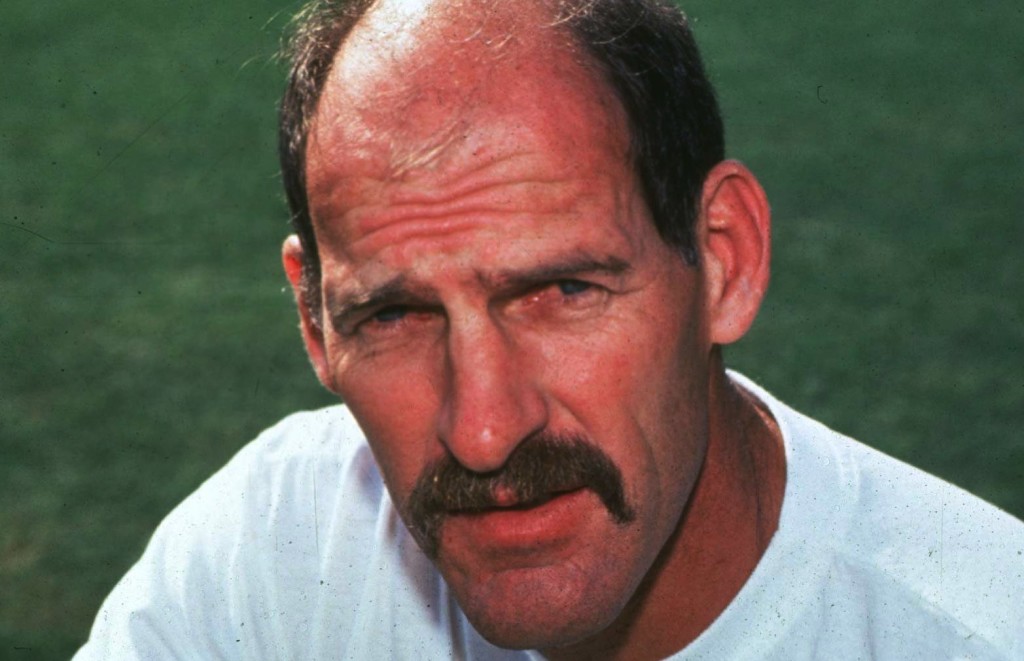

Clive Rice, the former Transvaal and South Africa captain, has died.

It is understood he developed a serious bowel infection. SACricketmag.com broke the story on Tuesday morning.

The 66-year-old iconic cricketer recently underwent a procedure on a cancerous brain tumour in India after doctors in South Africa told him there was nothing they could do and he was going to die.

Rice was diagnosed with the tumour after collapsing in February. The prognosis after the treatment was good, and he even gave an interview, saying: ‘From being in a state where they told you, you’re basically going to die, well, that’s what we’re all going to do. But I’m not in a hurry to die,’ Rice said. ‘Through this treatment we managed to sort it out.’

Rice had robotic radiation treatment, a procedure where a machine sends radiation into the brain using lasers to destroy the tumour without needing to cut into the brain.

Rice’s career coincided directly with South Africa’s sporting isolation, and his international experience was limited to his post-prime days.

He played three One Day Internationals for South Africa following the country’s return from sporting isolation – against India in 1991.

Mere months later he was controversially left out of the squads for the one-off Test against the West Indies and the 1992 Cricket World Cup.

Rice played 482 first-class games in a career that spanned some 24 years. An all-rounder, Rice amassed 26 331 first-class runs at an average of 40.95, including 48 hundreds and 137 fifties. As a seamer, Rice claimed 930 wickets at 22.39.

Through the 1970s and 80s, for Transvaal and Nottinghamshire, he was one of the game’s leading all-rounders – a punishing right-handed batsman with one of the most savage cuts in cricket, a seamer capable of genuine pace through the 1970s and a captain as hard-headed as any in the business.

He attracted the attention of Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket – recognition of his abilities – and was an automatic choice for the South African teams against the rebel tourists of the 1980s. He was also the epitome of the modern professional cricketer, quick to recognise the financial opportunities that began to arise in the game.